There's a tweet making the rounds right now. Andrej Karpathy wrote:

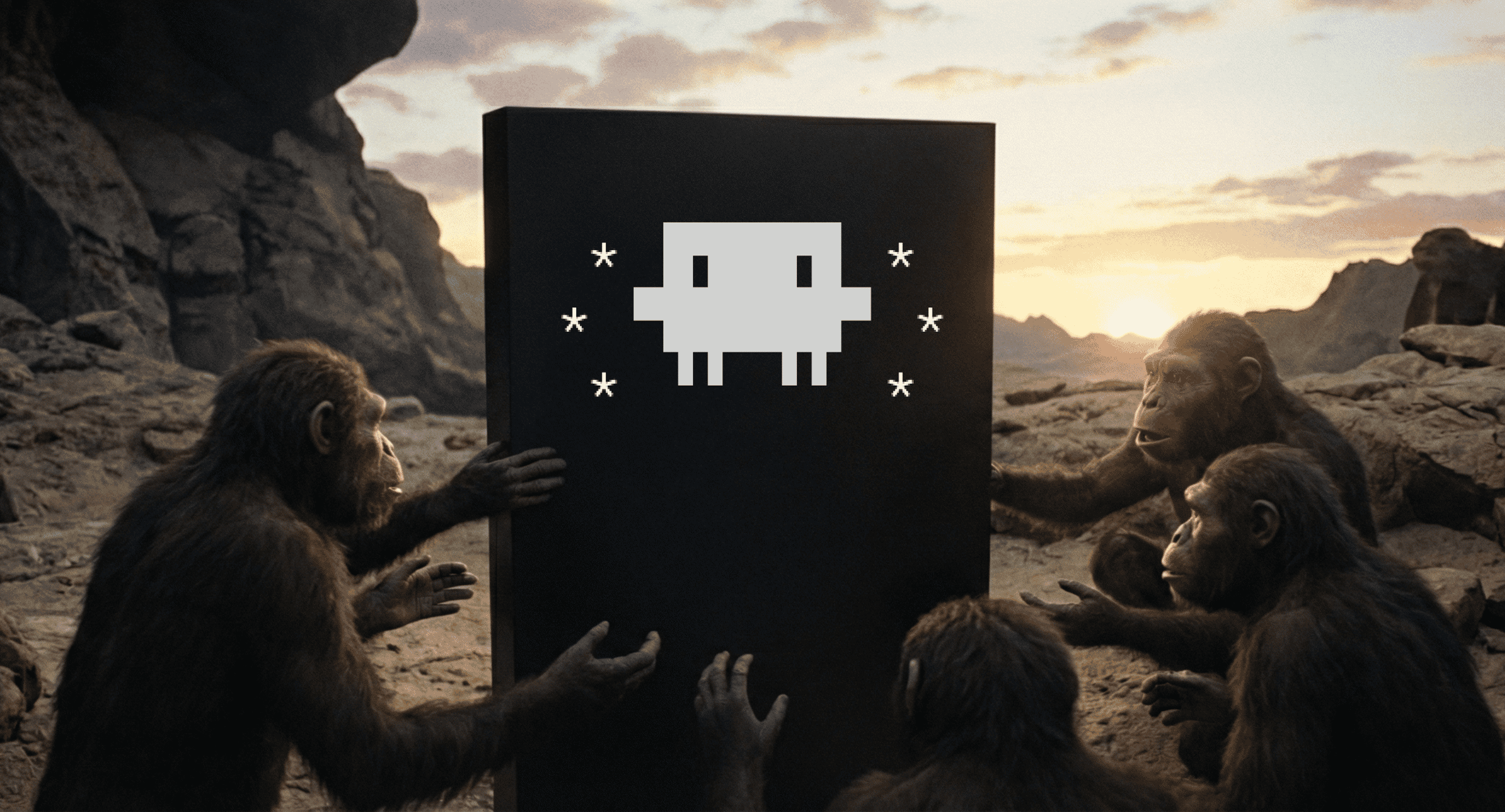

I've never felt this much behind as a programmer. The profession is being dramatically refactored as the bits contributed by the programmer are increasingly sparse and between. I have a sense that I could be 10X more powerful if I just properly string together what has become available over the last ~year and a failure to claim the boost feels decidedly like skill issue. There's a new programmable layer of abstraction to master (in addition to the usual layers below) involving agents, subagents, their prompts, contexts, memory, modes, permissions, tools, plugins, skills, hooks, MCP, LSP, slash commands, workflows, IDE integrations, and a need to build an all-encompassing mental model for strengths and pitfalls of fundamentally stochastic, fallible, unintelligible and changing entities suddenly intermingled with what used to be good old fashioned engineering. Clearly some powerful alien tool was handed around except it comes with no manual and everyone has to figure out how to hold it and operate it, while the resulting magnitude 9 earthquake is rocking the profession. Roll up your sleeves to not fall behind.

Boris Cherny, who created Claude Code, responded:

I feel this way most weeks tbh. Sometimes I start approaching a problem manually, and have to remind myself "claude can probably do this". Recently we were debugging a memory leak in Claude Code, and I started approaching it the old fashioned way: connecting a profiler, using the app, pausing the profiler, manually looking through heap allocations. My coworker was looking at the same issue, and just asked Claude to make a heap dump, then read the dump to look for retained objects that probably shouldn't be there; Claude 1-shotted it and put up a PR. The same thing happens most weeks.

In a way, newer coworkers and even new grads that don't make all sorts of assumptions about what the model can and can't do — legacy memories formed when using old models — are able to use the model most effectively. It takes significant mental work to re-adjust to what the model can do every month or two, as models continue to become better and better at coding and engineering.

The last month was my first month as an engineer that I didn't open an IDE at all. Opus 4.5 wrote around 200 PRs, every single line. Software engineering is radically changing, and the hardest part even for early adopters and practitioners like us is to continue to re-adjust our expectations. And this is still just the beginning.

One is trying to make sense of the change. The other is living on the other side of it. Everyone's talking about this. But to me something's missing from the conversation—something about what it feels like to use these tools well, and why some people might click with them while others don't.

Late 2022, sitting on a plane at Heathrow. I saw the tweet that OpenAI had just released ChatGPT and immediately felt that pull—I had to try it. Thinking about what I could ask it, I had wanted something to read on the flight. I gave it a few authors I love—Alastair Reynolds, Greg Egan—and asked what else I might like.

It suggested Ted Chiang's "Stories of Your Life and Others."

I'd heard of Chiang but never read him. I bought it for my Kindle, started reading as we took off, and didn't stop until we landed. It was exactly right. Not just a reasonable suggestion—it understood something about what I was looking for. Compared to what we have access to now, it was simple but hugely impactful for me.

Since then, my entire relationship with how I work has changed. I use AI in nearly every part of my professional life (and many parts of my personal life). I have always loved the craft and act of writing code, but underneath that is a bigger love for systems—the design of things, how pieces fit together, the foundatioal architecture. I was trained as a designer before I became an engineer. AI didn't replace the parts I love. It amplified them.

But not everyone has this experience. Some people try these tools, bounce off, and conclude they're overhyped. Others—often people you'd expect to be great at it, senior engineers with deep expertise—struggle more than you'd think.

I have a theory about why.

When working with AI, the skill that matters most isn't prompt engineering. It's not about finding magic words or optimal templates. The real skill is the ability to put yourself in the agent's position—to model where it is in its thinking, understand why it went in a particular direction, and then adjust your framing to guide it somewhere else.

You have to hold your idea loosely enough to explain it multiple ways—and notice when the agent misunderstood, asking yourself why. Not "this is stupid, it didn't get it," but "what did I say that led it there, and how do I say it differently?"

I've often thought about this through a metaphor that's helped me in other parts of my life.

Imagine whatever you're trying to communicate—an idea, a design, a piece of software you want to build—as a 3D object floating in space. When you describe it one way, you put a single light on it. You illuminate one face. The agent sees that face and responds to it.

But the object has other sides you haven't lit up yet.

When you rephrase, when you come at it from a different angle, you're not repeating yourself. You're adding another light. You're illuminating another part of the shape. Say it enough ways, from enough angles, and eventually the whole object becomes visible.

I first developed this way of thinking in the context of my personal relationships. In hard conversations, saying something once is rarely enough. We all have different internal dictionaries. The first way you phrase something might land completely differently than you intended because the other person is mapping your words onto their own meanings.

So you say it again, differently. Not because they didn't hear you, but because language is only ever a shadow of the thing you're actually trying to convey. Multiple shadows from multiple angles give you the shape.

The same thing applies to working with AI. When you prompt once, the agent only has one angle on what you want. The real work happens in the dialogue that follows—refining, reframing, approaching from different directions.

And the thing you're building changes through that process. You're not transferring a fixed idea from your head into the machine. You're co-constructing. You start with a sense of what you want, you articulate it, you see how the agent interprets it, and that reflection shows you something about your own idea that you hadn't fully seen.

This is how life works. Relationships are ongoing work. Understanding is ongoing work. This is just another instance of the same thing.

The dialogue isn't overhead before the work. The dialogue is the work.

There's a Hacker News comment I share with people when I'm trying to explain the ways AI can genuinely help across basically all areas of work. It's from a professional translator describing their actual process:

I run the prompt and source text through several LLMs and glance at the results. If they are generally in the style I want, I start compiling my own translation based on them, choosing the sentences and paragraphs I like most from each. As I go along, I also make my own adjustments to the translation as I see fit.

When I am unable to think of a good English version for a particular sentence, I give the Japanese and English versions of the paragraph to an LLM and ask for ten suggestions for translations of the problematic sentence. Usually one or two of the suggestions work fine; if not, I ask for ten more.

They call it "using an LLM as a sentence-level thesaurus on steroids."

Look at what they're actually doing. They're running translations through multiple models. They're comparing outputs, selecting sentences they like from each, combining them. When they get stuck on a single sentence, they ask for ten variations, then ten more if needed. They cycle through different models multiple times. They even run the final version through text-to-speech to hear it aloud and catch awkwardness they might miss reading silently.

This is not "AI replaced the translator." This is someone using AI to see more angles than they could see alone. Their taste, their judgment, their deep knowledge of both Japanese and English—that's what makes the whole thing work. The AI doesn't replace their expertise. It gives them more surface area to apply that expertise to.

That word—taste—matters. Ira Glass has a famous quote about creative work:

All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it's just not that good... It's trying to be good, it has potential, but it's not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer.

This applies directly to working with AI. The tool can generate endless variations, but you need the taste to know which ones are good. You need the judgment to recognize when something is close but not right. Without that, you're just accepting whatever comes back. With it, you're using the tool to explore a space you couldn't explore alone.

So why do some people struggle with this?

Boris had an insight in his tweet that keeps coming back to me: "Newer coworkers and even new grads that don't make all sorts of assumptions about what the model can and can't do—legacy memories formed when using old models—are able to use the model most effectively."

There's something painful about this if you're an experienced engineer. You've spent years building intuitions about how software gets made. You know the right ways to structure things, the patterns that work, the pitfalls to avoid. That knowledge is incredibly valuable.

Except when the paradigm shifts.

When you start using these AI tools with strong priors about what they can and can't do, you tend to use them in ways that confirm those priors. You expect the tools to be a fancy autocomplete, so you use them like one, and you get autocomplete-quality results. You measure their output against your internal template of how things "should" be done, and when it doesn't match, you conclude it's not that useful.

Meanwhile, someone with less experience but more openness just... tries things. They ask for something ambitious. They see what happens. They adjust. They're not fighting against expectations because they don't have the same expectations to fight.

But expertise matters. Taste. Architectural judgment. The ability to recognize when the agent is confidently wrong—and it will be, sometimes, confidently wrong.

The goal isn't to abandon your experience. It's to hold it differently. Use it as a compass, not a cage.

Openness without expertise creates bugs. You'll accept things you shouldn't accept, miss problems that experience would have caught. But expertise without openness creates friction. You'll fight the tools, limit what you try, and miss what's actually possible now.

You need both. High openness and deep experience, held lightly.

I have friends who are skeptical of all this. And honestly, I get it more than they might think.

AI slop is real. I notice it now when I'm scrolling Twitter—something in the cadence, the emptiness, the way it says a lot without saying anything. It's everywhere, and it's genuinely damaging. I hate it. Part of why I'm writing this is because I want to help people understand how to avoid producing it.

But here's the irony I keep noticing: many of the people who critique AI for being shallow are engaging with it shallowly. They prompt once, get back something generic, and say "see? Slop." They treat it like a vending machine, get vending-machine results, and then conclude that's all it can do.

The shallow engagement produces the shallow output. And then the shallow output becomes the evidence that AI is shallow.

And underneath the specific objections, there's a deeper fear: that AI is going to make us passive. That we'll stop thinking for ourselves. That we'll become dependent on machines for the thing that makes us human.

I understand that fear. But it assumes a passive relationship with the tool—you type, it outputs, you accept. In that model, yes, you're not thinking. You're outsourcing cognition and accepting whatever comes back.

But that's not how it works when you actually engage with it.

When you work with AI the way the translator does, the way I've learned to—you're constantly thinking. Articulating your ideas, watching how they reflect back. Noticing when the agent misunderstood and asking why. Holding multiple directions in your head, choosing between them. Refining your own understanding through the act of trying to communicate it.

The process requires more thinking, not less.

AI doesn't think for you. It's a surface you think against. The fear of passivity describes a version of AI use that the best practitioners simply aren't doing.

And it doesn't replace working with other people. You can do both. If anything, using AI well gives you more to bring to human collaboration—clearer thinking, better-articulated ideas, more angles explored before you even start the conversation.

A few weeks ago, someone on my team had an annoying manual workflow—something repetitive that ate time and attention. Before, building an internal CLI to solve that would have been a project. I would have had to weigh whether it was worth the investment, scope it out, find the time. It probably wouldn't have happened.

Instead, I built it in a few hours. After spending time with the agent clarifying what we needed, what edge cases to handle, how it should work—the actual code came together fast. A bespoke piece of software that solved a real problem, built in an afternoon.

This is the shift. The bottleneck used to be how much code I could write. That's not the bottleneck anymore.

Now the bottleneck is knowing what to build. Having the judgment to focus on the right thing. Making sure the direction is correct before you go fast in it. The work moved up the stack—from execution to intention.

That's not a smaller job. It's a bigger one.

Remember the tweet we started with? The "alien tool with no manual," the "magnitude 9 earthquake"? The ground really is shifting.

But the people worried about AI making us passive have it backwards.

The risk isn't that AI will do your thinking for you. It's that you'll let it—and that's on you. If you engage shallowly, you'll get shallow results. If you treat it like a vending machine, you'll get vending-machine output. The slop people complain about isn't a property of the tool. It's a reflection of how most people use it.

But if you engage deeply—if you bring your taste, your judgment, your willingness to keep illuminating the shape until you can see it clearly—something else opens up.

You can build things that would have taken weeks in an afternoon. Explore ideas you wouldn't have had time to pursue. Bring clearer thinking to every conversation because you've already stress-tested your ideas against a surface that pushed back.

Boris hasn't opened an IDE in a month. That's not because he stopped thinking. It's because he's thinking at a different level—deciding what to build, not just how to build it.

That's the shift. The bottleneck moved. And now the question is whether you'll move with it.

More thinking, not less.